Overview

A Musico-Logical Offering

The book opens with the story of Bach’s Musical Offering. Bach made an impromptu visit to King Frederick the Great of Prussia, and was requested to improvise upon a theme presented by the King. His improvisations formed the basis of that great work. The Musical Offering and its story form a theme upon which I “improvise” throughout the book, thus making a sort of “Metamusical Offering”. Self-reference and its interplay between different levels in Bach are discussed; this leads to a discussion of parallel ideas in Escher’s drawings and then Gödel’s Theorem. A brief presentation of the history of logic and paradoxes is given as background for Gödel’s Theorem. This leads to mechanical reasoning and computers, and the debate about whether Artificial Intelligence is possible. I close with an explanation of the origins of the book – particularly the why and wherefore of the Dialogues. (p. viii)

Topics

The Introduction covers a large number of topics, very briefly, giving a taste of what the book is about. Each of these topics will be covered in greater detail later on.

Bach (p. 3)

Musical Offering - The Royal Theme

Frederick the Great asked Bach to improvise on this difficult theme.

The video to the right visualizes the Royal Theme, the melody that Frederick the Great asked Bach to improvise upon. Bach went beyond that, and made it the basis of his entire Musical Offering (BWV 1079), parts of which will appear throughout GEB. The Royal Theme is difficult to work with, including a long sequence of consecutive chromatic notes, and not exactly pleasant on its own, which makes it quite impressive that Bach was able to make a suite of good music out of it.

Something odd about the Musical Offering is that Bach seems to have designed it to be appreciated as sheet music first, and as an audible performance second. Bach never specifies what instruments should perform each piece, and many of the pieces within it are notated as puzzles. The tricks involving putting too many clefs on one staff, indicating that you play the same part multiple ways, aren't just an invention of GEB. This is how Bach really notated the music.

You can find the sheet music for the Musical Offering in various forms, both in Bach's original handwriting and in cleaned-up typesetting, on IMSLP. This PDF, for example, is Bach's manuscript for five of the canons plus one fugue.

Canons and Fugues (p. 8)

Canon on "Good King Wenceslas"

Hofstadter describes this canon by inversion at the top of p. 9.

At the top of page 9, Hofstadter uses "Good King Wenceslas" as an example of a canon, a musical piece where one part is an exact transformation of another part. The bottom part (in blue) mirrors the familiar melody (in green), but upside-down and two beats later.

An Endlessly Rising Canon (p. 10)

Bach - Musical Offering - Endlessly Rising Canon (Karl Richter)

Karl Richter conducts this performance of the "Endlessly Rising Canon", which in fact rises 6 times before ending.

The Musical Offering's "Canon 5 a 2", often called the "Endlessly Rising Canon", is a bit of a paradox in itself. How can a piece of music rise endlessly, when this means that eventually the notes will be too high for the instruments performing it? Any performance of this canon must end sometime, and most of them end after six repetitions. Because each repetition raises the pitch by a whole step, and six whole steps make an octave, six repetitions will bring the music back to its original key, but it's one octave higher. Some recordings repeat 12 times, ending two octaves higher with an overwhelmingly high-pitched sound.

The top voice performs the melody that's based on the Royal Theme, although it's in rearranged fragments.

A clever modern idea called the Shepard scale makes it possible to loop this music so that it "rises endlessly", without actually getting any higher in pitch in the long run. This appears much later in the book. If you're impatient, it's in Chapter 20, pages 717-719.

Escher (p. 10)

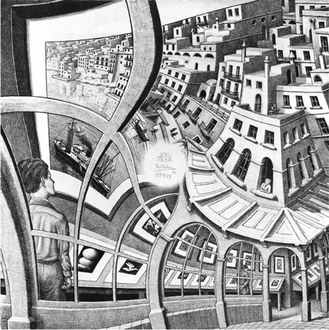

Escher's "Print Gallery" (1956)

This section mentions Escher's "Print Gallery", which appears to the right.

What happens at the very center of this picture? Some geometry is too confusing even for Escher, so he covered it up with a white circle and his signature.

Recently, however, some mathematicians at Leiden University came up with a transformation of the plane that reproduces the self-engulfing effect that Escher drew. Now you can see what happens at the center. Be sure to zoom in! Escher and the Droste effect

Gödel (p. 15)

After introducing Epimenides' famous statement, "All Cretans are liars", Hofstadter quickly replaces it with the more straightforward statements "I am lying" and "This statement is false".

There's a good reason to do this: Epimenides' original statement is actually not much of a paradox! It could be described as confusing and self-defeating, and furthermore it could be described as false. This is different from the liar paradox, "This statement is false", which is paradoxical because it cannot be consistently called true or false. This difference catches even experienced mathematicians by surprise.

If you assert that the Epimenides statement is true, then you're agreeing that Epimenides is a liar and that his statement should therefore be false, which is a contradiction. Sounds just like the liar paradox, right? But it doesn't work the other way. The Epimenides statement can be false, because its negation is "It's not true that all Cretans are liars", or "Some Cretans are not liars", or "A Cretan has told the truth at some point". This is true [citation needed], so it is consistent to say that Epimenides' statement is false.

Epimenides may be a liar, but against all intuition, he's a logically consistent one.

See also: ➟ Liar paradox

Mathematical Logic: A Synopsis (p. 19)

Banishing Strange Loops (p. 21)

Consistency, Completeness, Hilbert's Program (p. 23)

Babbage, Computers, Artificial Intelligence... (p. 24)

...and Bach (p. 27)

Gödel, Escher, Bach (p. 27)

Further reading

Easter eggs

- Author (p. 3)

- The first word in the book is easy to miss. It's "Author:".

- This odd self-reference serves two purposes. One of them is to point out the level of dialogue that's "outside the system". He labels the lines that Tortoise and Achilles say with "Tortoise:" and "Achilles:", as that's the entirely traditional convention that tells you which character is saying them. He wouldn't normally be expected to label the entire book with "Author:", because you just assume that a non-fiction book is what the author is saying. But he does, probably because looking for assumptions that come from "outside the system" is a major theme in the book.

- The other purpose is setting up for a payoff that will be delivered much, much later.

Commentary

(This section is for adding your thoughts about the chapter. Sign what you write with your user name. Others may edit this section for length later. More free-form, unedited discussion can take place in the comment section below.)